Wildlife

Thursday, 25 January 2001

The height of our summer is peak season for

Antarctic wildlife, and it is abounding everywhere these days.

It is wonderful.

The Great Skua birds are closely related to gulls,

but they are more stockily built and brown in color. They are very

aggressive birds. Skuas feed on young penguins, fish and plankton

from the sea, eggs and other small chicks, and even other young

skuas. They also scavenge through garbage cans around McMurdo. It

is against the Antarctic treaty for us to feed them, however, they

do not wait around for handouts. If they see food in your hand,

they will take it away.

Skuas spend their winter months at sea. It is

not certain just how far they travel, but some records show them

to have gone as far as the West Indies. They build nests out of

pebbles and bones, and will lay two spotted brown eggs, however

they generally will only rear the first chick to hatch. They

defend their territory ferociously.

Life is teeming under the ice. The divers are

the only people down here who really get an opportunity to see all

of that wildlife firsthand. However, many species have been caught

and are in our aquarium for observation. I apologize that not all

the photos are clear, but I have had a terrible time getting really

sharp photos at the aquarium The most popular items in the aquarium

are the Antarctic cod. These fish get to be more than 100 pounds.

The scientists study them for the antifreeze in the blood stream.

The reason they are so popular is that once they are through

studying them, we get to eat them. I have to say that this cod is

the best–tasting fish I have ever eaten. This season I even

had some sushi from the cod cheeks. Delicious!

Several other smaller fish are also in the aquarium. Nothing is

marked so knowing what things are is sometimes difficult. I like

the little fish with the curly tail. Some of them curl a couple of

times around.

Funny little bug–like creatures appear almost prehistoric to

me.

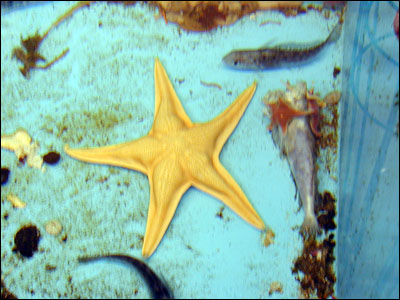

Sea Stars and a sea worm

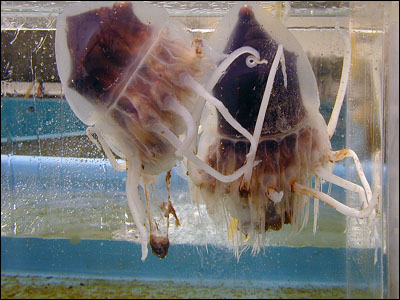

Jellyfish

Octopusses

Sea Spiders

Sea Urchins

Sea anemones

Sea stars

The big news this season is the appearance of a

skate — a kind of ray. This is the first skate ever caught

in McMurdo Sound. It is possible that they are prevalent in these

waters and only the use of a new, multiple–hook fishing

technique is what finally snagged them. The skate caught here is a

male weighing 25 pounds and measuring 3.7 feet long. It is possible

that this is an undescribed species, but this will not be determined

until many more tests have been done.

Weddell seals are the most common seals in this

area. They have a silver–grey coat spotted and blotched with

black, grey and white. These seals are among the best swimmers on

the planet. They dive in excess of 2,000 feet, exceed speeds of 6

metres per second, and can stay under the water without breathing

for over an hour. During the winter they live entirely under the ice,

chewing holes in the ice to breathe. Older seals often have broken

and abscessed teeth from several years and grinding and gnawing

the ice.

Weddell seals breed under the water. In the

summer months they will venture on to the surface and lounge and

sleep on top of the ice. There they become lazy and complacent.

Scientists take advantage of this time to tag the seals.

These seals are very unconcerned about humans, rarely responding

when one walks by. Occasionally they will sit up and take notice.

Female Weddell seals give birth on top of the

sea ice. They will stay on top of the ice with their young through

the entire suckling period, which means they go without food

throughout that time.

Seal pups weigh 55–65 pounds when born, but they grow quickly.

By the time they are entirely weaned, approximately six weeks, they

can weigh up to 200 pounds. During this time the mother will have

lost twice what the baby seals gain.

Young Weddell seals take to the water almost immediately and can

become independent within two to three months.

Crabeater seals, while being possibly the most

numerous of all the world's seals, are rare to the McMurdo area.

Little is known of this species of seal. It is suspected that they

may be monogamous, which is rare for seals, as they are often seen

in small family groups. They tend to be much slimmer than Weddell

seals, although generally around the same length — 10 feet

from nose to tail. Unlike the Weddell seals that feed on fish,

Crabeater seals feed entirely on krill. They are generally grey

along the spine, turning to tan along the sides and belly.

Emperor penguins are remarkable birds. While

they are somewhat clumsy on the surface, they are superb swimmers,

diving as deep as 1,500 feet. They breed on the pack ice and are

the only species of bird that never sets foot on land.

The males incubate eggs for 65 days through the long, harsh winter

months, in temperatures as low as –45°C. During this time

the males fast, losing as much as 40% of their body weight. The

females spend this time at sea. They return in mid–July,

just as the chicks are hatching. Young chicks lose their down and

become fully fledged within five months.

By mid–December they will have reached 60% of their adult

body weight.

One of the science teams found several emperor

chicks that had been abandoned. They built a couple of pools in

the sea ice where they could raise them and teach them to swim.

We had an opportunity to go out and see them. They have 10 young

adults out there. They have already shed their down layer, but do

not yet have the coloring of the adult penguins.

Watching Adelie penguins without laughing is

impossible. They are highly animated and childlike in their

curiosity.

When nest–building in the spring, male penguins find it quite

acceptable to steal pebbles and rocks from other Adelie nests, but

become somewhat irate when they find they have been stolen from.

As with all penguins, Adelies are excellent swimmers.

Like Emperor penguins, male Adelies are the ones

to incubate the eggs, also fasting for several weeks. By the time

the females return from the sea, the males will have lost half their

early–season weight. As the sea ice begins to break up, food

supplies get nearer. In the last 3–4 weeks of incubation the

females will return and alternate incubating every three to four

days, allowing the males to seek out food. After hatching they

continue to share responsibilities, alternating at 3–4 day

intervals.

It is still a little early to be seeing the

whales as the sea ice has not gone out completely. Instead, here

is a little wildlife of the manmade variety.

|